Native Habitat: Status and Trend

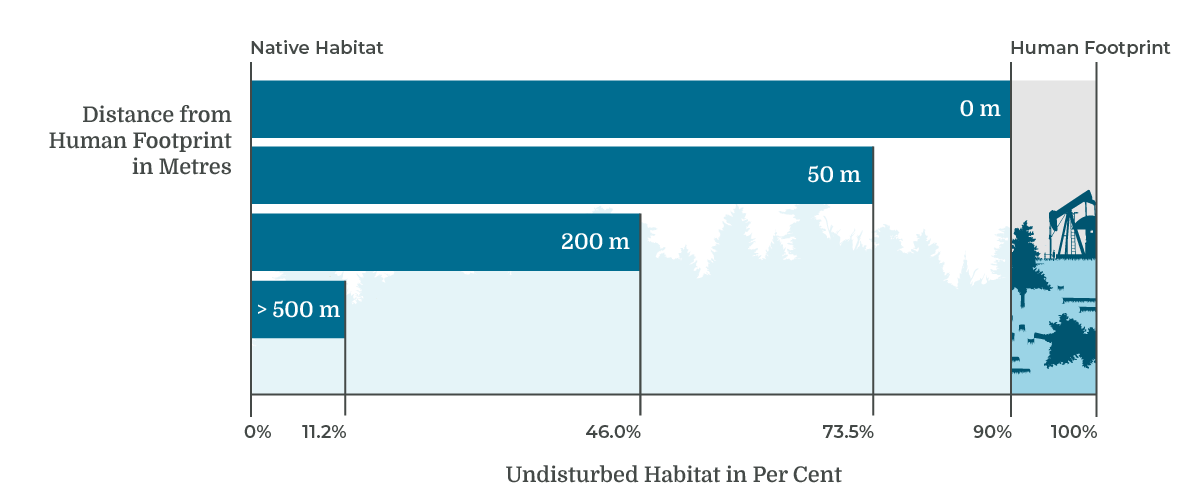

Summary of the status (circa 2021) and trend (2010–2021) of native habitat in Tolko's Northern Operating Area, including interior native habitat at 50 m, 200 m, and 500 m away from human footprint.

Native Habitat

- Interior native habitat was 73.5%, 46.0%, and 11.2% at 50 m, 200 m and 500 m away from human footprint respectively.

- The distribution of linear footprint is the primary factor reducing the area of interior habitat.

- 3.3% of native habitat was converted to human footprint between 2010 and 2021. White Spruce and mixedwood stands were the vegetation types most impacted by human footprint in this timeframe, resulting in more edge habitat and less interior habitat compared to other vegetation types.

Introduction

Undisturbed natural areas, or native habitats, are important to maintain biodiversity and ecosystem functions[1]. Habitat loss due to human disturbance is a primary threat to biological diversity[2].

- In addition to the direct loss of native habitat, proximity of human footprint can change environmental conditions in nearby native habitat, known as edge effects, indirectly impacting biodiversity.

- Some wildlife species, such as the Dark-eyed Junco and Chipping Sparrow, can use habitat that is adjacent to human footprint[3]. Other species prefer habitat that is more distant from human footprint, Woodland Caribou being the most well-known example.

- Most measured ecological edge effects have effective distances <50 m from human footprint, with a few extending 200 m or more. The distance of 500 m is generally well away from any edge effects, although there are still some broader regional effects of footprint, such as introduction of non-native species, altered fire regimes, and access for hunting.

- Within its Northern Operating Area, Tolko has established a target that the area of old interior forest will not be less than 80% of projected old interior forest from year 10 of the spatial harvest sequence[4]. This target is assumed to be met if the spatial harvest sequence is adhered to within 20%, and was on track as of 2022[5].

Status and trend of native habitat and interior native habitat at three distances (i.e., 50 m, 200 m, 500 m) from human footprint is summarized for Tolko’s Northern Operating Area.

Dark-eyed Junco can tolerate some habitat alteration.

_Rangifer%20tarandus%20(2)_3862x2415_432x432.jpg)

Woodland Caribou is associated with undisturbed coniferous forests and peatlands.

Many lichens, such as Gray's Pixie-cup, are sensitive to disturbance.

Results

Status of Native Habitat

The status of native habitat (circa 2021) at increasing distances from human footprint in the Northern Operating Area was:

0 buffer

50-m buffer

200-m buffer

500-m buffer

Highlights

- Native habitat covers 90.0% of the Northern Operating Area.

- About three quarters of the Northern Operating Area is interior native habitat at least 50 m from human footprint, which decreases to 46.0% at least 200 m from human footprint. 11.2% of interior native habitat is at least 500 m from human footprint.

- Human development activities occur throughout the Northern Operating Area. It is the distribution of this footprint, especially linear footprint, throughout the landscape that contributes to the fragmentation of native vegetation, reducing the area of interior native habitat.

Change in the Area of Interior Native Habitat: 2010–2021

- Between 2010 and 2021, 3.3% of native vegetation was converted to human footprint. This affected the area of interior habitats: the area more than 500 m from human footprint decreased from 13.8% in 2010 to 11.2% in 2021, and the area more than 200 m from human footprint decreased from 51.4% in 2010 to 46.0% in 2021.

- Most direct impacts of human footprint were on upland vegetation (-7.8%), but lowland areas also lost some interior habitat (0.2%) over that time span. That may be due to linear features in lowlands, or edge effects from human footprint in adjacent upland areas.

- As shown in Section 2.2, White Spruce and mixedwood stands were the vegetation types most impacted by human footprint from 2010 to 2021, resulting in more edge habitat and less interior habitat compared to deciduous and pine stands.

- While all stand types lost interior area over that span, this was mainly due to overall loss of the native vegetation, rather than an increasing percentage of edge effects.

Change in Interior Native Habitat

Change in Interior Native Habitat. For the Northern Operating Area, the change in the area of interior native habitat from 2010 to 2021, expressed as a percentage of the total area of undisturbed vegetation in 2010, measured at four distances from human footprint: 0–50 m (lightest green), 50–200 m, 200–500 m, and >500 m (darkest green). Hover over each segment of the bar for a summary of: 1) the percentage of native vegetation area at the selected distance from human footprint, and 2) the percentage of native vegetation within each distance category (i.e., 0–50 m, 50–200 m, 200–500 m, and >500 m).

References

Potapov, P., M.C. Hansen, L. Laestadius, S. Turubanova, A. Yaroshenko, C. Thies, W. Smith, I. Zhuravleva, A. Komarova, S. Minnemeyer, and E. Esipova. 2017. The last frontiers of wilderness: tracking loss of intact forest landscapes from 2000 to 2013. Science Advances 3(1):e1600821.

Sanderson, E.W., M. Jaiteh, M.A. Levy, K.H. Redford, A.V. Wannebo, and G. Wolmer. 2002. The human footprint and the last of the wild. Bioscience 52(10):891-904.

Bayne, E., H. Lankau, and J. Tigner. 2011. Ecologically-based criteria to assess the impact and recovery of seismic lines: the importance of width, regeneration, and seismic density. Report No. 192. Edmonton, AB. 98 pp.

Tolko Industries Ltd., Norbord Inc., and La Crete Sawmills Ltd. 2017. Forest management plan. Forest management plan submitted to Alberta Agriculture and Forestry December 2017 for FMU26. 375 pp.

La Crete Sawmills Ltd., Tolko Industries Ltd., and West Fraser. 2023. F26 stewardship report 2017–2022. Report developed with Silvacom. 117 pp.