Tracking the Recovery of Woodland Caribou Habitat

Testing methods to measure caribou habitat recovery using remote sensing data.

This section is a summary of results presented in Dickie et al. 2023 [1]

- Habitat restoration is essential for Woodland Caribou population recovery.

- This study explored how remote sensing tools can be used to track vegetation regrowth in caribou range.

- Results show that vegetation is recovering faster in harvested areas compared to other disturbance types.

- Overall, the study provides a method to distinguish between areas naturally regenerating and those needing restoration to support regrowth.

Introduction

Woodland Caribou populations are declining across much of western Canada, including in the seven ranges that overlap Tolko’s operating areas in Alberta—this species is federally listed as Threatened in Alberta because of these declines.

In this section, we highlight results of a study[1] testing the application of photogrammetry (extracting 3D information from aerial photographs) and lidar (light detection and ranging) data as tools to measure and monitor the recovery of vegetation in two caribou ranges—Chinchaga and Caribou Mountains—that overlap Tolko’s operating areas. While this technique was applied to just two of the caribou ranges that overlap with Tolko's Northern Operating Area, the methods are widely applicable across all caribou ranges.

At Issue

The condition of habitat is, in part, implicated in Woodland Caribou declines because:

- Wolves, a primary predator of caribou, use linear features like seismic lines, pipelines, and roads to travel “faster and farther”, increasing their hunting efficiency[2];

- These linear features serve as access routes into previously inaccessible caribou habitat, decreasing spatial separation between caribou and their predators[3];

- Human footprint associated with industry (e.g., forest harvesting, seismic lines) results in the conversion of old forests to early seral habitats which supports higher densities of primary prey, such as moose and deer[4,5,6,7]; higher prey densities support increased numbers of wolves in caribou ranges, increasing the mortality risk of caribou.

Ultimately, the combined interaction of these factors has altered predator-prey dynamics in caribou range, increasing caribou mortality risk.

Linear features like seismic lines...

...allow wolves to move quickly across the landscape...

...increasing mortality risk of caribou

Habitat Management Goals

Habitat restoration has been identified as a key management measure to improve forest regeneration and restore predator-prey interactions to support the recovery of caribou populations[8].

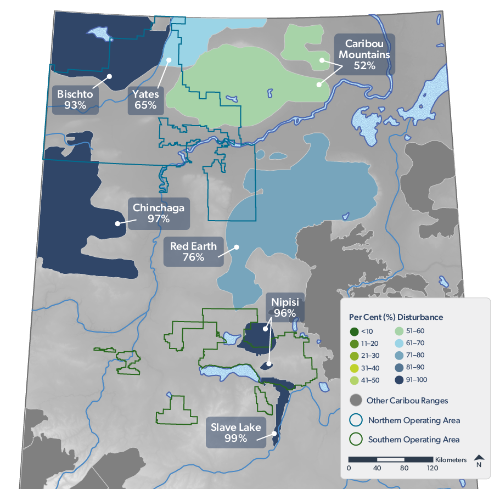

- Environment and Climate Change Canada[9] requires that habitat disturbance levels, including natural (i.e., fire) and human disturbance, not exceed 35% in each caribou range.

- All caribou ranges that overlap with Tolko’s operating areas are more than 50% disturbed, with levels of >90% disturbance in four ranges (Bischto, Chinchaga, Nipisi, and Slave Lake).

- Defining and monitoring recovering habitat is an area of active research in Alberta to not only identify those areas that are contributing toward the goal of 65% undisturbed habitat, but also to identify areas that are not regenerating and may require restoration efforts.

About Remote Sensing Methods to Monitor Habitat Recovery

Remote sensing is the science of collecting data about the Earth's surface from a distance, typically using satellites or planes.

- Advanced remote sensing techniques can be used to inventory and monitor habitat at large scales[10], including evaluating the restoration and recovery of caribou habitat.

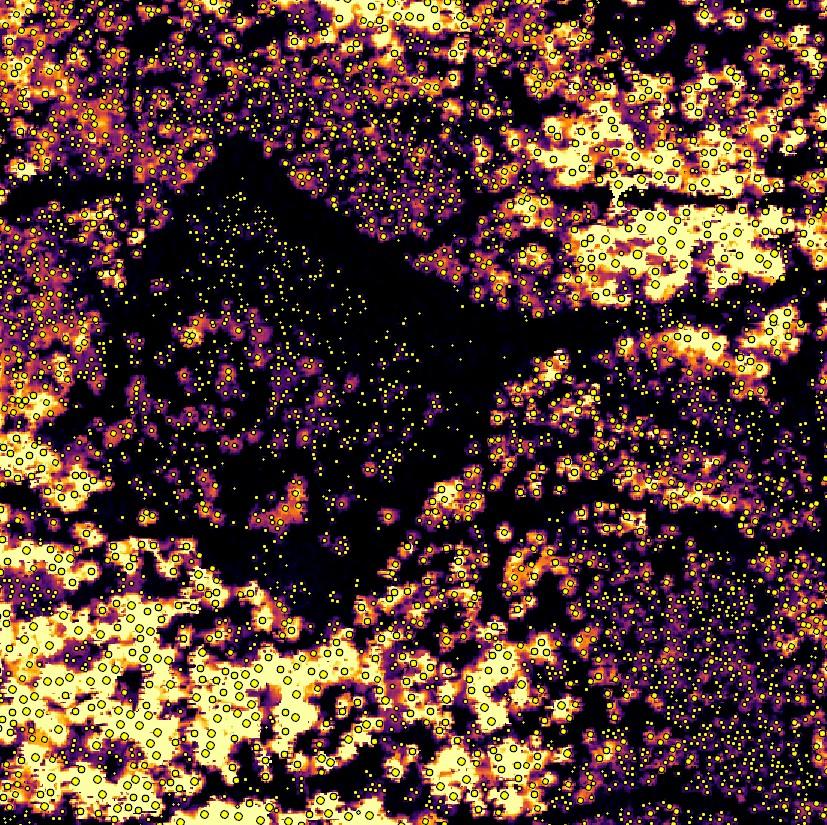

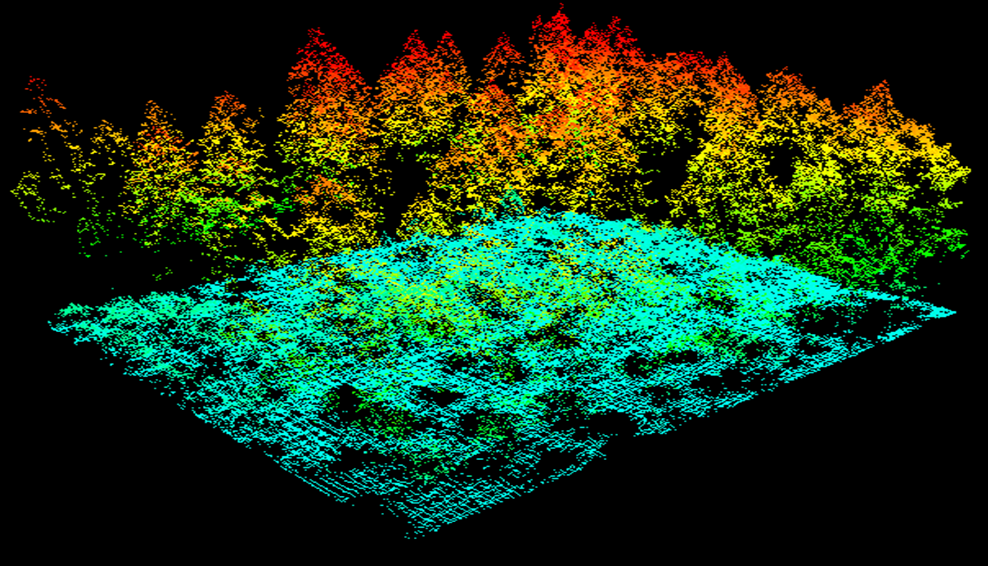

- In this study, two scanning technologies, photogrammetry point clouds and lidar, were used to assess habitat recovery in two caribou ranges that overlap Tolko’s Northern Operating Area—Chinchaga and Caribou Mountains.

- Photogrammetry point clouds were fused with lidar data to measure vegetation structure, specifically vegetation height, density, and class of shrubs and trees (e.g., deciduous, coniferous) in different disturbances (e.g. forest harvest areas, seismic lines) related to caribou declines.

- For detailed methods see Dickie et al. 2023[1].

Aerial photos taken from different angles...

...were used to generate 3D models of vegetation in caribou ranges

Results Highlights

Vegetation regrowth is occurring on many of the footprint types; but some footprint is recovering more slowly than others.

- Harvest areas had taller vegetation (average median height >4 m) compared to other footprint types, and average tree density was also the highest at >1700 trees/ha.

- The majority of seismic lines had vegetation heights below 1.5 m. In addition, the dominant vegetation type on most lines was shrubs, or a mix of shrubs and bryophytes; the percent area of seismic lines covered by conifer and/or deciduous was <10%.

- Well pads and pipelines had intermediate levels of vegetation regrowth compared to harvest areas and seismic lines, with average vegetation height ≥1.9 m. Average tree density on pipelines was >1000 trees/ha on pipelines but was typically <1000 trees/ha on well pads.

Lidar generates high-resolution aerial imagery that maps the physical features of a landscape, producing a detailed point cloud representation of the land surface.

Management Implications and Next Steps

- This study demonstrated that integrating photogrammetry and lidar data provides high-resolution remote sensing information that can effectively estimate habitat recovery rates in caribou range.

- This approach helps identify areas on a successful recovery trajectory and prioritize disturbed regions that may need restoration to support vegetation regrowth. The development of metrics to assess recovery using this method is ongoing.

- Tolko is collaborating with the Alberta government and other industry partners to develop regional Woodland Caribou recovery plans.

References

Dickie, M., B. Hricko, C. Hopkinson, V. Tran, M. Kohler, S. Toni, R. Serrouya, and J. Kariyeva. 2023. Applying remote sensing for large-landscape problems: inventorying and tracking habitat recovery for a broadly distributed species at risk. Ecological Evidence and Solutions 4(3):e12254. https://doi.org/10.1002/2688-8319.12254

Dickie, M.R., R. Serrouya, R.S. McNay, and S. Boutin. 2017. Faster and farther: wolf movement on linear features and implications for hunting behaviour. Journal of Applied Ecology 54(1):253-263.

DeMars, C.A. and S. Boutin. 2018. Nowhere to hide: effects of linear features on predator-prey dynamics in a large mammal system. Journal of Animal Ecology 87(1):274-284.

Bergerud, A.T. and J.P. Elliot. 1986. Dynamics of caribou and wolves in northern British Columbia. Canadian Journal of Zoology 64:1515-1529.

Seip, D.R. 1992. Factors limiting woodland caribou populations and their interrelationships with wolves and moose in southeastern British Columbia. Canadian Journal of Zoology 70:1494-1503.

James, A.R.C., S. Boutin, D.M. Herbert, and A.B. Rippin. 2004. Spatial separation of caribou from moose and its relation to predation by wolves. Journal of Wildlife Management 68:799-809.

Latham, A.D.M., M.C. Latham, N.A. McCutchen, and S. Boutin. 2011. Invading white-tailed deer change wolf-caribou dynamics in northeastern Alberta. The Journal of Wildlife Management 75:204-212.

Environment and Climate Change Canada. 2020. Agreement for the conservation and recovery of woodland caribou in Alberta. Report available here.

Environment Canada. 2012. Recovery strategy for the Woodland Caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou), boreal population, in Canada. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Environment Canada, Ottawa, ON. xi + 138 pp.

Bhatt, P., A. Maclean, Y. Dickinson, and C. Kumar. 2022. Fine-scale mapping of natural ecological communities using machine learning approaches. Remote Sensing 14(3): 563. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14030563